Journalists know this drill: Bad News is Good News.

It is a distorted viewpoint, yes, but it is true for us. You see, journalists live for “crisis moments,” especially those undetected, spontaneous sort — the sort that “write themselves” as we like to say. They spare us the tiring work of searching for newsworthy stuff, of probing into clandestine deals or the routine and boring beat coverage, or the oft-fruitless spadework to confirm a lead.

On the contrary, a crisis moment unexpectedly falls on our laps like manna from heaven. It induces in us an adrenaline rush that gives birth in our aroused minds to a dozen other corollary and auxiliary stories, which are, in turn, covered from a host of different angles, enough to fill one hour of newscast on the day the crisis breaks, and half-a-newscast every day for many days, even weeks, on end. It leaves us breathless!

Yes, we live for these moments. No, we don't delight in them. But they do give us a sense of gratification in doing what we are empowered to do. We are able to justify and validate our significance. (Yes, we need that validation, especially when we feel burnt out, which happens quite often.) And while all crises are heartbreaking, perplexing, risky, and just plain difficult to cover sufficiently and accurately, they remind us of who we are and why we do what we do. Most of all, they propel us back to the fervor of our first love: reporting.

But this coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a crisis all its own. COVID-19 is its own media censor. It literally stopped us from covering it firsthand. For the first time, we had a dearth of story takers. There were so few volunteers. Several of us had to be quarantined for having been contact-traced. Some were feeling paranoid about their cold and cough and decided they would rather take a sick leave.

“ In our shared paranoia, we felt powerless. But then, like weeds, the journo in us stubbornly refused to be pulled out of the ground. ”

A few others, like myself, had comorbidities (let alone senior or near-senior status) and were forced to work from home. And the rest — especially the field reporters and crews — were not too willing to risk getting COVID-19, not so much to shield themselves but their families and housemates.

They only returned to work after they were given room and board in a COVID-free establishment within the epicenter that is NCR. That took some doing.

COVID-19 had us all on the same boat as everyone else.

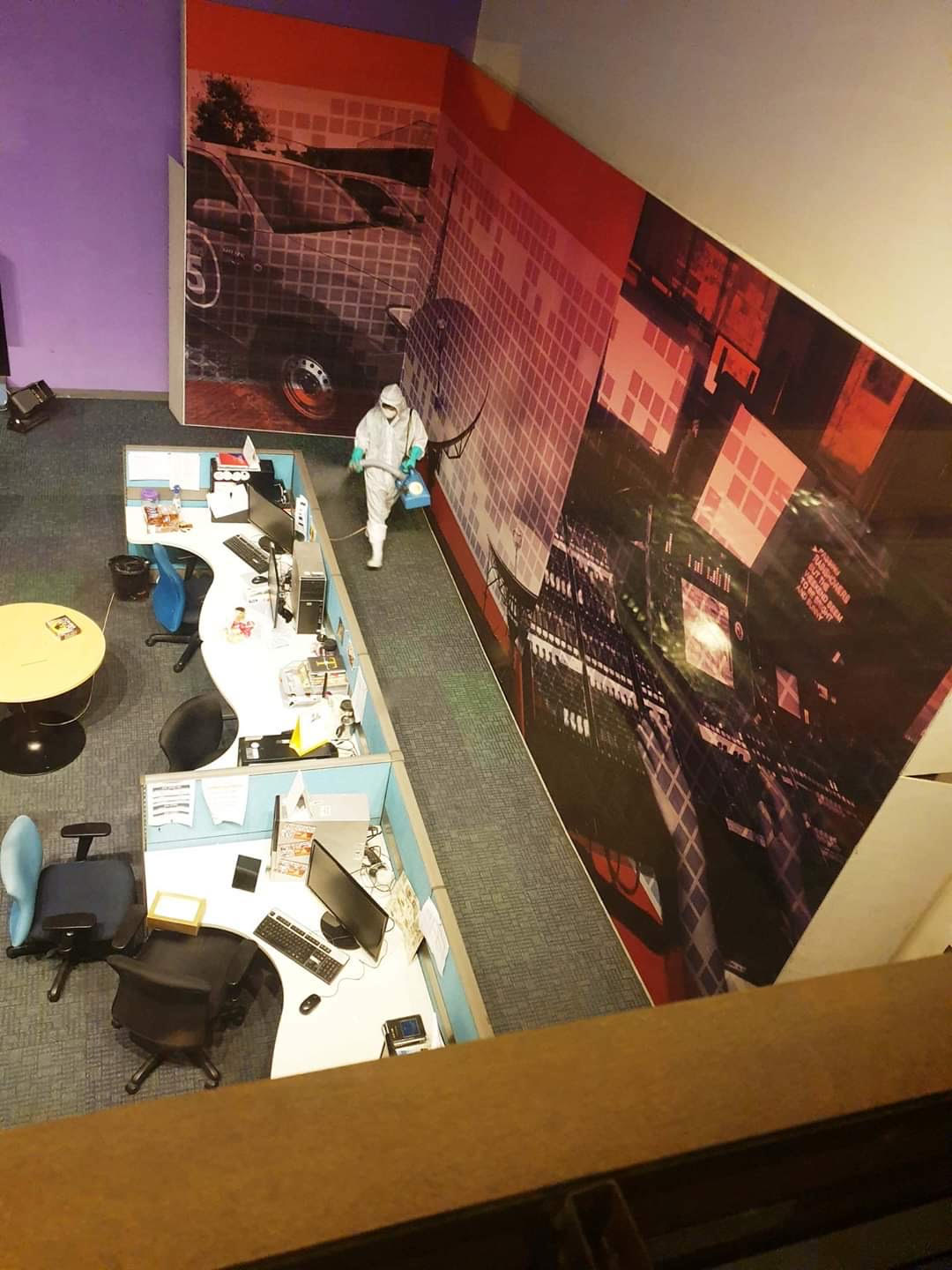

In our shared paranoia, we felt powerless. But then, like weeds, the journo in us stubbornly refused to be pulled out of the ground.We put up a skeleton staff to man our newsroom operations and production. The staff comprised a mere one-fifth of our regular manpower count, and they voluntarily locked themselves in the newsroom 24/7 for two weeks, alternating with a second team to take over.

As for the rest of us, we took stock of what we had and what we could do, putting to use our array of personal resources to continue churning out news stories to fill airtime. Reporters created chat groups with their news contacts as a way to get news leads. Producers combed social media and the web for stories “na pwedeng patayuin.”

“ There are several absolute truths here worth pondering: the truth that despite the great strides we have made in practically all fields of endeavor, we can still be rendered helpless. The truth that there is still so much that we don't know and understand, let alone resolve. The truth that we are all still living in this one planet despite our differences, and the most challenging truth of all — that we must work together even if we can't stand each other. ”

Interviews were 100-percent virtual. And while these interviews have their advantages — they're more intimate, less intimidating, not time-bound, interviewees could be notes-supported or aided on the side — I do miss the “gulpe de gulat,” in-your-face, spur-of-the-moment ambush interviews that often elicited great soundbites (SOTs in broadcast lingo).

For the desk and online editors who are the second line of gatekeepers of the news, work has multiplied exponentially. Not only do they have to monitor, screen, and edit the stories submitted by our field reporters, but the bulk of their charge is now trained on the information coming out of the black hole that is social media and the world wide web.

I wager that 50 percent of the desk's work has now shifted to online searching, fact-checking, confirming, or flagging fake news. This is an absolutely arduous task. And if only for this, I take my hat off to story editors. You will lead the way to the new normal, guys!

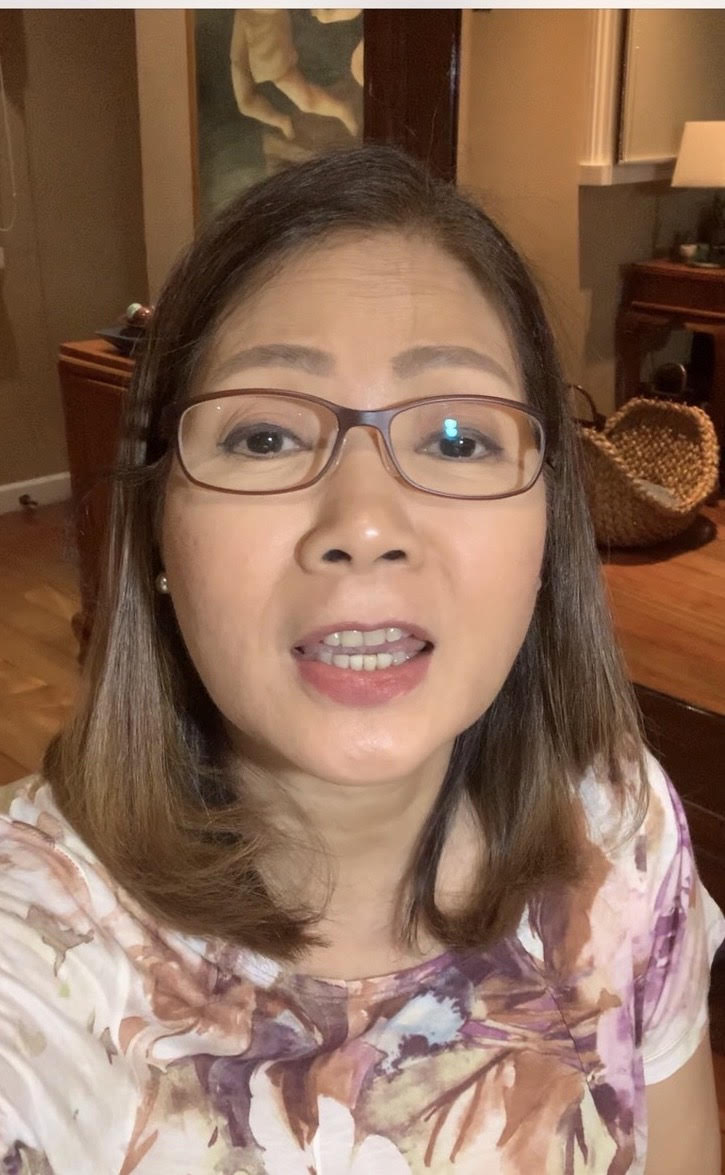

Anchors have had to make some adjustments as well. Sure, they are just mostly surface adjustments but they are still tough in their own way. We have had to buckle down to work, converting desks or nooks in our homes into a broadcast-worthy mini-studio or download chroma-applicable backdrops where we could.

The hardest part, though — especially for those of us not naturally blessed with visually pleasant faces — is going on camera sans makeup and groomed hair. I now have to do off-cam work that I never bothered doing on my own before COVID-19, for instance, dyeing my own hair to cover up the exposed gray roots.

It's a good thing though that it is easier to choose an outfit now because we only have to look dressy on the upper part of our body while wearing our usual plop-on-couch casual and our usual flip flops from the waist down.

The biggest upside to me, however, is how this whole COVID-19 crisis has been humbling. And then again, that's what truth never fails to do — that is, if we allow it. There are several absolute truths here worth pondering: the truth that despite the great strides we have made in practically all fields of endeavor, we can still be rendered helpless. The truth that there is still so much that we don't know and understand, let alone resolve. The truth that we are all still living in this one planet despite our differences, and the most challenging truth of all — that we must work together even if we can't stand each other.

Truths like these should give us pause and make us ask the one question that needs to be asked: Is there really a power way beyond our reach, calling us to turn to Him for the answer? For those who believe, it’s all good.

Edited by Tanya T. Lara